Tyneham - Where Time Stopped in 1943

Oooh – do you mind just backing up? I said to Arthur as he drove the van carefully up a narrow, bushy road in South East England. Typical me, I had spotted a large manor house in the valley beside us and couldn’t pass by without a photo. He pulled to the side, and I jumped out with my camera. The next few miles would play out as they always do when I spot some historical place that grabs my interest – I would search the internet for context, and spend the next few miles regaling the details to my captive audience.

Apparently, I am not the only person who must stop and photograph every manor house along the route; another woman stepped up beside me. Creech Grange, she said in a broad British accent, motioning toward the mansion, saving me a google. Owned by the same folks what owned the Manor at Tyneham. She snapped a few pictures. Are you going to Tyneham? She asked. Clearly, she thought I knew what Tyneham was. No, we’ll be camping around here, on Steeple Leaze Farm, I replied. Well, you should, she said, it’s just along this track. Military road is open. It’s not always open. You should go. She jumped into her car and drove off.

As we entered the farm gate at Steeple Leaze a few minutes later, I spotted a small white-painted board in the shape of an arrow, nailed to a tree and pointing onward along the one-track road. The black lettering read Tyneham. I made a mental note to follow it in the morning. At the farm, we learned we were on the edge of a sizeable military zone, the Lulworth Ranges, and occasionally, when the military was on hiatus, you could venture in, carefully keeping to the roadways and marked trails to avoid stepping on unexploded shells. Rightio.

In 1943, the allied forces laid out the plans for Operation Overlord, or, what we remember as D-Day, and they needed a place for training exercises. The wide-open spaces and beaches of south Dorset, just across the channel from Normandy, were ideal, except for one thing – Tyneham. This small village, which dates back more than a thousand years, even mentioned in The Domesday Book – the Great Survey of England in 1086, was in the way.

The following day we drove past a heavy steel gate, open, but not welcoming, sporting a sign warning us of the dangers of straying from the marked route. We kept carefully to the barbed wire lanes while our GPS insisted we turn around - these routes didn’t exist on our maps. The grassy hills rolled to the sea, void of anything but a few shrubs and a scattering of rusty army tanks. And then, in a lush green valley, the road ended at a stone village - a few cottages, a schoolhouse, and a church.

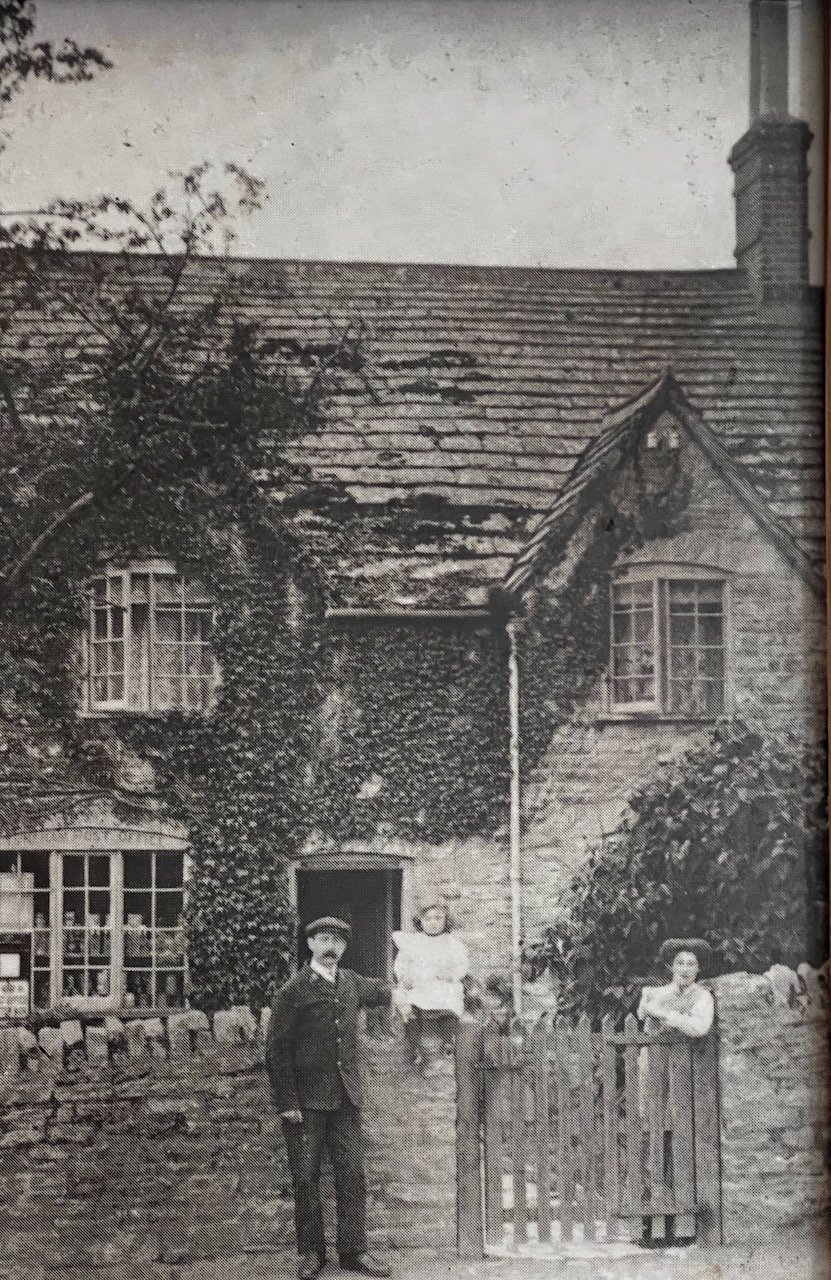

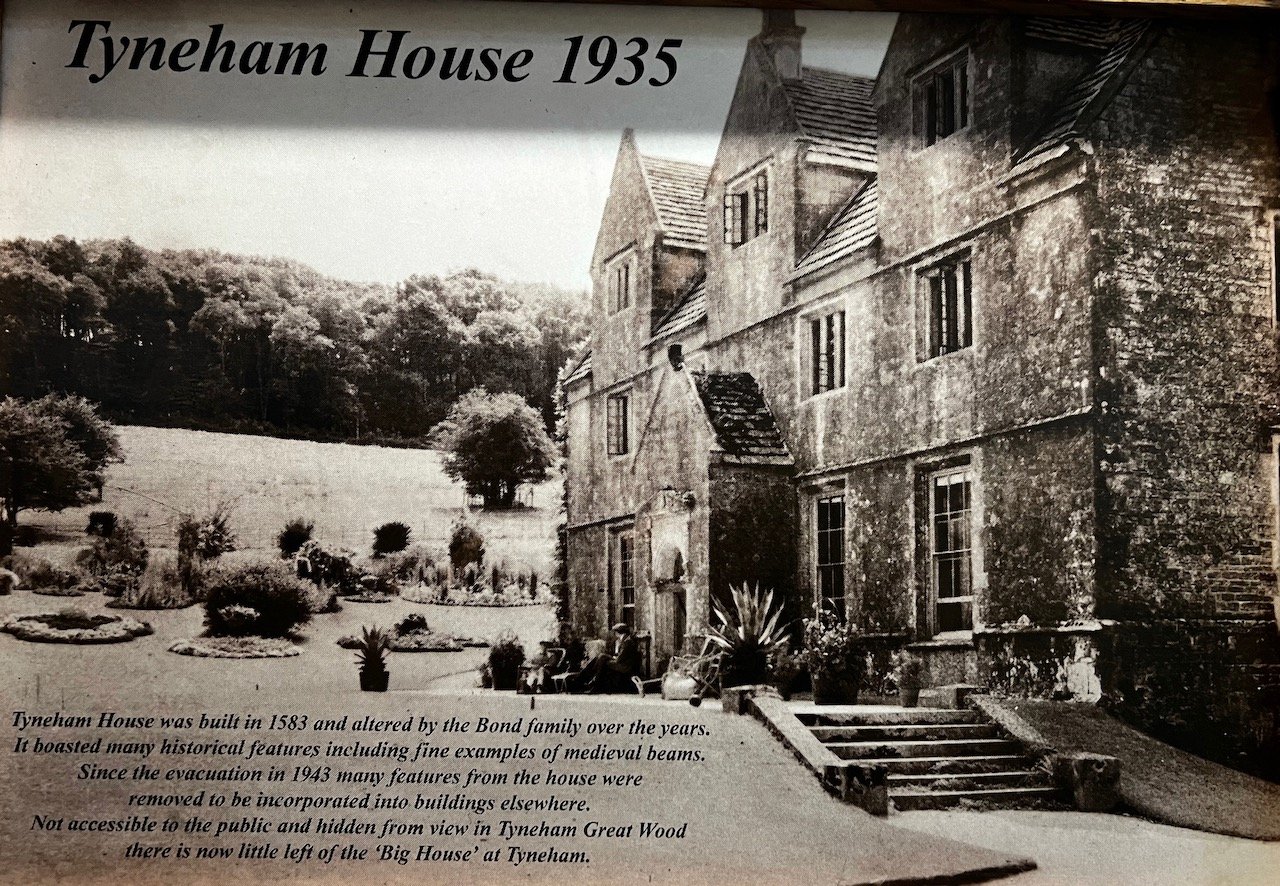

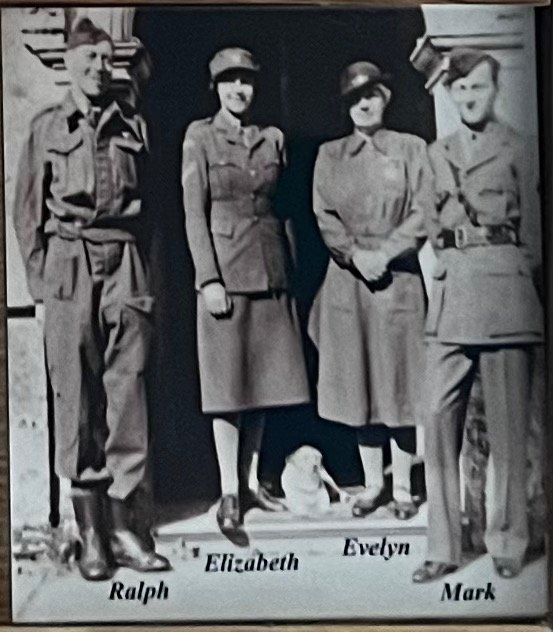

Tyneham had belonged to the Bonds. (They were the same folks what owned Creech Grange). Back in 1683, Nicholas Bond bought it and became Lord of the Manor. He and his Bond offspring lived in Tyneham House while collecting rents from the tenant farmers and fishermen. The whole package, village, farms and manor, passed down from generation to generation for more than 250 years, and in 1935 Ralph inherited it. In 1941, Ralph and his wife Evelyn loaned the mansion to the war effort as a residence for the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, and moved into the old gardener’s house nearby with their daughter Elizabeth. Mark, their 18-year-old son had enlisted in 1940.

On November 16, 1943 every mail-box in Tyneham received a letter from Churchill’s War office:

In order to give our troops the fullest opportunity to perfect their training in the use of modern weapons of war, the army must have an area of land particularly suited to their special needs and in which they can use live shells. For this reason you will realize the chosen area must be cleared of all civilians. […]

It is regretted that, in the National Interest, it is necessary to move you from your homes, and everything possible will be done to help you, both by payment of compensation and by finding other accommodation for you if you are unable to do so yourself.

The date on which the military will take over this area is the 19th December next, and all civilians must be out of the area by that date. […]

The Government appreciate that this is no small sacrifice which you are asked to make, but they are sure that you will give this further help towards winning the war with a good heart.

No reason was given because of the secrecy surrounding D-Day. They were to be out the week before Christmas.

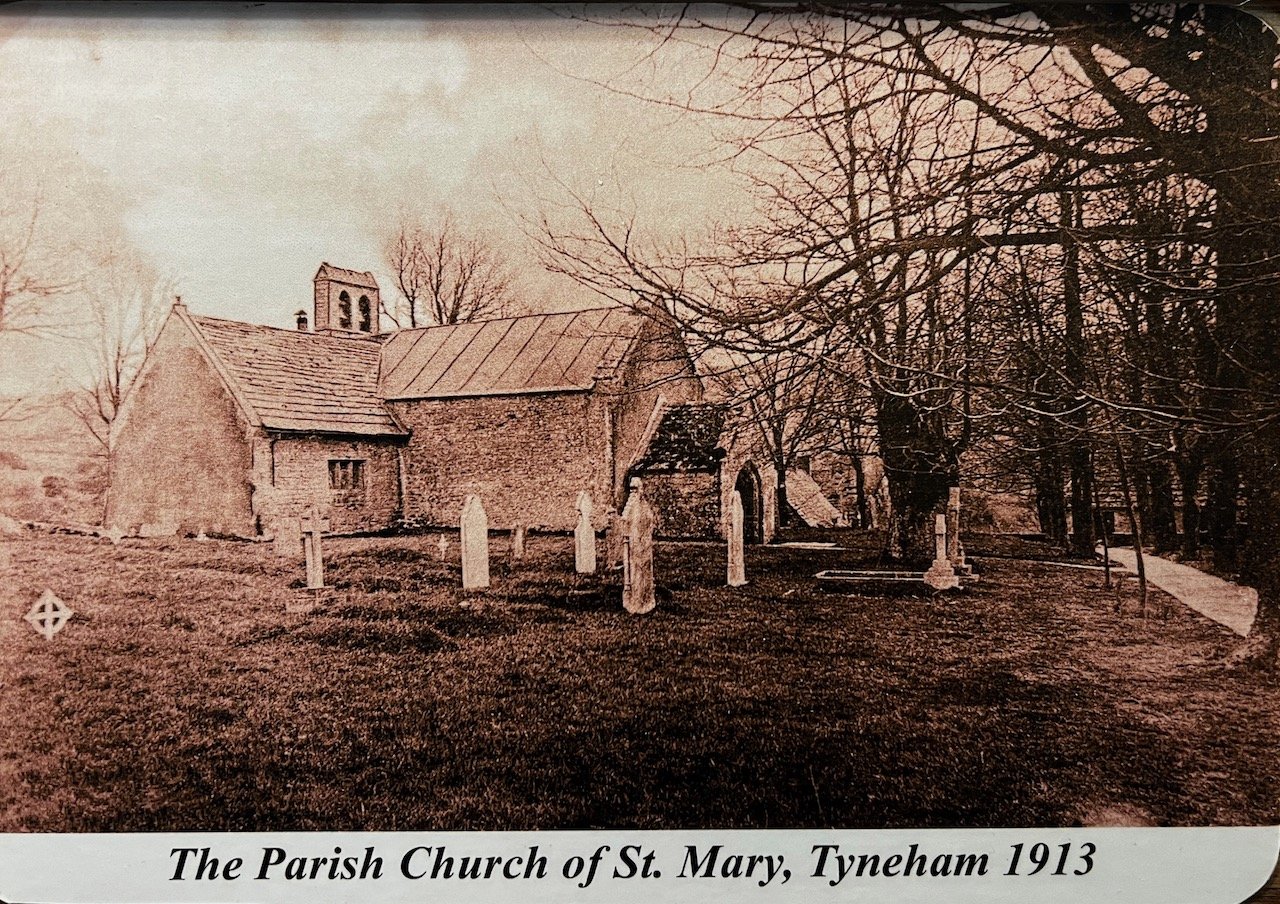

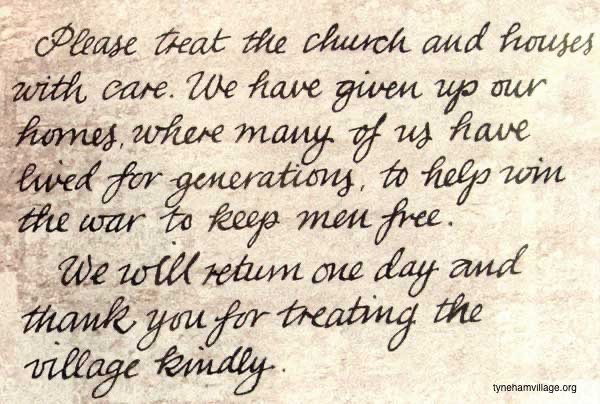

December 19th was a particularly melancholy day for Evelyn Bond - on that very day she received news that Mark had been taken prisoner by the Germans. Coming home again was evidently on her mind as she made one last stop before leaving the village - to post a note to the church door:

Please treat the church and houses with care. We have given up our homes where many of us have lived for generations to help win the war to keep men free. We will return one day and thank you for treating the village kindly.

Initially, the 225 residents of Tyneham were assured this was a temporary measure and they could return after the war. But, post-war, with the demands of the Cold War upon them, the government reneged on their original proposal and kept the land for military use. Mark survived the war, and lived until 2017, but not as the next Bond of Tyneham.

We began to explore the crumbling ruins. Roofless walls with empty eyes where once were windows. Placards with “before” photos and resident stories to help with perspective. We followed a trail from the main village road into the surrounding wooded acreage, where a few larger houses stood in equal decay. One thing was conspicuously missing - Tyneham House, with its 16th-century architecture and 14th-century Medieval Great Hall. Maybe down this trail? I dragged Arthur deeper into the woods. Surely it wouldn’t be that far from the village? I expected it around every bend in the forest path but came up empty-handed. And then, sadly, a display in the church told me it had been left to rot into the ground in a forested area on the “other side” of the barbed wire. Inaccessible. Seriously! I couldn’t even hunt down the foundation and had to satisfy myself by finding the location via satellite. I stood at the edge of the abyss looking in the general direction, embellishing the landscape with my imagination.

The Bonds were bought out for £30,000. The other residents were tenants; they had no ownership. They were compensated for the value of the vegetables in their gardens. It was December – what was chard worth in 1943? But the villagers had liked living there, that is clear from the interviews I read, and although they enjoyed the running water and electric lights in their replacement houses, they fought for years, without success, to come back to Tyneham. As the 1943 residents passed away over the decades, many were laid to rest in the church graveyard, a homecoming of sorts?

Was Tyneham treated kindly, as requested by the note on the door? The church is intact, as is the little schoolhouse. Some homes were ruined by artillery fire, others by the elements. But the barbed wire did save it from the infringing tourism industry so evident in the surrounding areas. It’s a place frozen in time. The past preserved by cutting off the future.

On June 6, 1944, more than 156,115 Canadian, American and British troops, fortified by 6,939 ships and landing vessels, 2,395 aircraft and 867 gliders, stormed Normandy’s beaches, an operation that proved to be a critical turning point in World War II. D-day is largely considered the beginning of the end of World War II, and much of the success is attributed to preparation. 4,414 Allied troops lost their lives that day.

Lest we forget.