Hidden Amsterdam

Come this way! Arthur pulled me through a stout arched-wooden door into a short tunnel. It was my first trip to Amsterdam nearly two decades ago, and he was showing me all of his favourite corners. At first, I thought he was pulling me out from in front of another annoyed, bell-ringing cyclist – I was one of those tourists who kept stepping in front of bikers, causing them to slam the brakes and mumble something like hotferdomuh - but, instead, we appeared to be walking under a building. We emerged into a big bright courtyard surrounded by tall houses. Listen, whispered Arthur. I don't hear anything, I whispered back. Exactly! He smiled, looking satisfied with his answer. We had just left behind a bustling square, traversed by rattling trams and mad cyclists, and here, just a few steps away, we stood in silence. After my first trip through the tunnel, I was hooked on hidden Amsterdam.

That special place is the Begijnhof. Hof, meaning courtyard, and Begijnen, the community of single Catholic women who have lived there for 600 years. If you've asked me what to do in Amsterdam, I've sent you there. But, what I've discovered since, is that there are many more hidden sites in the city, just waiting to be explored by curious history buffs like me. Most of the hidden infrastructure dates back to the Golden Age when wealthy merchants poured their extra guilders into church and charity. Catholics, forbidden to worship in plain sight after the Reformation, built churches hidden away in regular-looking houses or behind facades resembling other buildings, adhering to the out-of-sight-out-of-mind principle. I've visited the three churches that are open to the public. One is smack in the middle of the red-light district, built in 1661; it literally hangs from the rafters of a tall canal house. Another is in the Begijnhof! I totally missed it on my first visit; that's how hidden it is. The third is on a popular shopping street, the narrow door easily passed by while searching for bargains. Sir Wealthy Merchant was also committed to providing homes for the underprivileged, in the form of the hof, or hofje (hofyuh) - a diminutive version of the hof.

Amsterdam city blocks are lined with stately houses that face outward, standing shoulder-to-shoulder, creating an impenetrable rectangular form. Typically, the centre is just a mash of back-yards, but sometimes, hidden inside that blocky shape is a left-over hof, originally designated to a group important to the merchant who founded it; Corvershof – 1723, older Dutch Reformed couples; Concordiahofje – 1864, working-class families; Deutzenhofje – 1695, elderly servants and poor relatives. By the middle of the 1700s, there were 28 hofjes in Amsterdam, and by the early 1900s, there were 58. Inhabitants were expected to follow rules, such as "to be honest and of good conduct, and have a peaceful temper."

In 1755, Gerrit ten Sande and his wife Maria de Groot built the Nieuwe Suykerhofje to house 54 elderly Catholic women in 27 rooms. They were a family of sugar-refiners, therefore the name, New Sugar Courtyard. It was a lovely little place, modern for the day. The rooms were stacked in six tall houses with big bright windows. Each room had a built-in double box bed, a display cabinet and a fireplace. At the back of the property was a bleaching field, common at the time to lay out linens in the sunshine. 22 years later, in 1777, Gerrit and Maria took their charity a step further and built what looked like a garden house on the field - it was, in fact, a clandestine chapel.

The hofje was operated by the family and heirs for over 150 years. But, in 1936, the last residents left when the health authorities designated it a slum complex. There was no running water and just one outhouse to serve all 27 rooms.

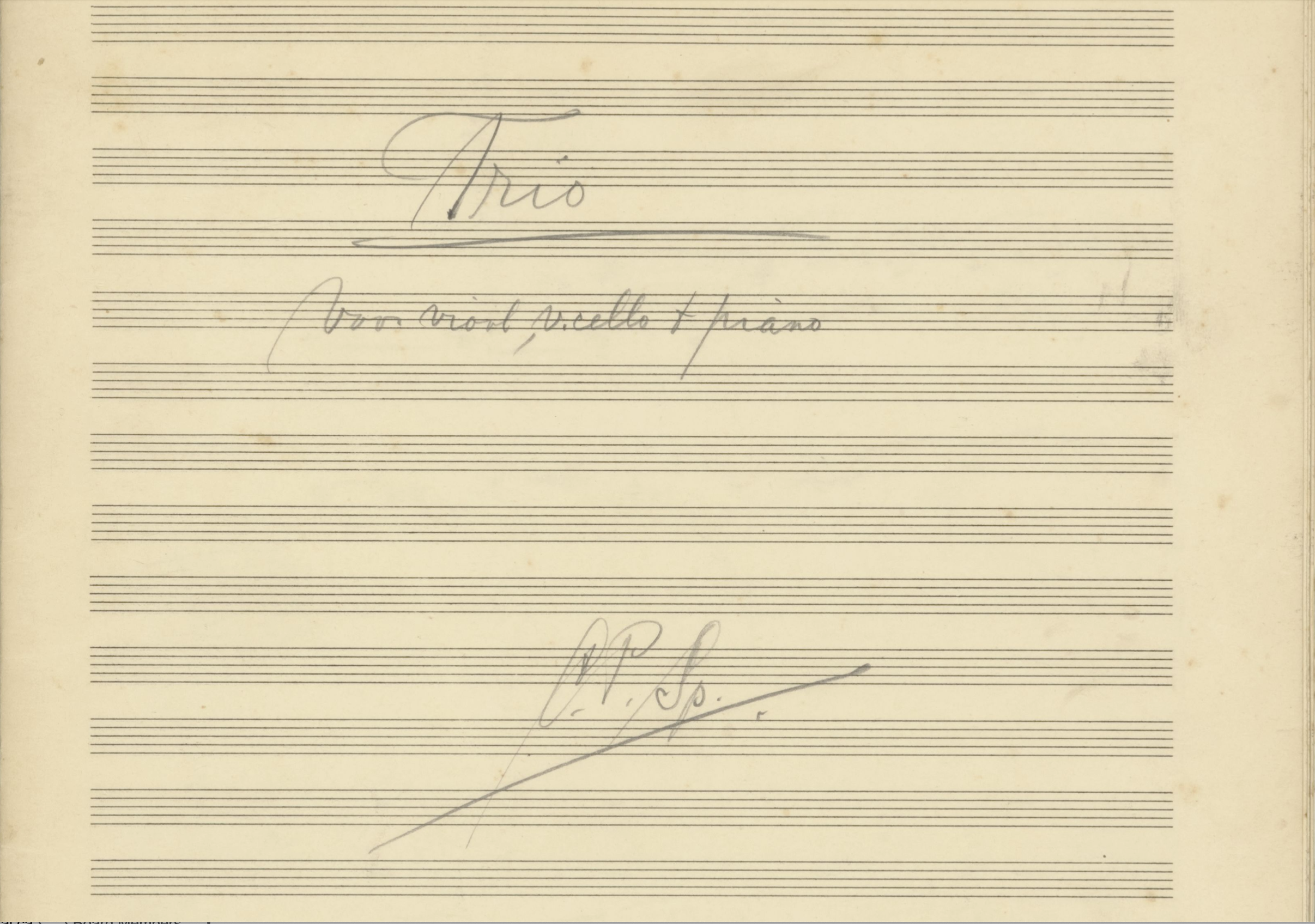

I only learned about the Nieuwe Suykerhofje because a couple of years ago, Arthur programmed a piece of music for violin, cello and piano that Jewish composer Bob Hanf composed, while in hiding from the Nazis. The music score did not name Bob Hanf as composer, but rather C.P. Sp. was scrawled across the title page, short for Christiaan Philippus Spinhoven, the name on his fake identity card. While I did enjoy his music, I found myself drawn to the story of his hiding place. I looked at a satellite image of the area and pinpointed the row of accordion-like orange roofs tucked deep behind a house facing the Prinsengracht, noting that Mr. Hanf was hiding just a few hundred metres from Anne Frank.

Curious about what now lay under the row of roofs, I snooped around and found an advertisement in an archived newspaper, the Volkskrant, October 29, 1938:

The Nieuwe Suykerhofje on Prinsengracht will soon cease to exist. It has been put up for auction and sold for 3701 guilders. In recent years the almshouse has gradually become more unpopulated, there was no longer any interest in it, and financial difficulties seem to have arisen as a result. It is now likely to be demolished.

But, history told me that it had not been demolished because Bob had lived there. The new owner, it turns out, opted not to tear the place down but instead, rent the rooms out to students for cheap – 3 guilders per room per month – about $2. After all, what can you get for a decrepit housing complex with one loo?

One of the students, Henk Pelser, wrote about living there in his book, Henk's War. I ordered it from his daughter, and since then, we've become digital pen-pals. They called it "Het Prinsenklooster" (The Prince's Monastery) she wrote to me, where Herman Maillette de Buy Wenniger [Henk's life-long friend] was the Abbot, and my father was Canon of Impractical Matters. Just as in the past, residents had to possess appropriate qualities, this time, "kindness, reliability, a sense of humour and a sense of community". And here, the story gets even more interesting. Many of these students, not on purpose, per se, but in an effort to help those around them, became part of the Dutch resistance during the war, each in his or her own way. From this hidden courtyard, Henk developed the escape route known as The Swiss Road, a line of farms and village houses with contacts willing to help Jews and others sought by the Nazis to safety in Switzerland. He checked the route regularly, re-routing as necessary as contacts became insecure, or worse, they were arrested. He, and others, distributed illegal magazines, including De Waarheid (The Truth), and Het Parool (The Password, which is still a mainstream newspaper today). They forged identity cards and passports and hid people at the Hofje before escorting them out of the country.

In his post-war book about the resistance, In de mist van het schimmenrijk, W.F. Hermans describes the Nieuwe Suykerhofje:

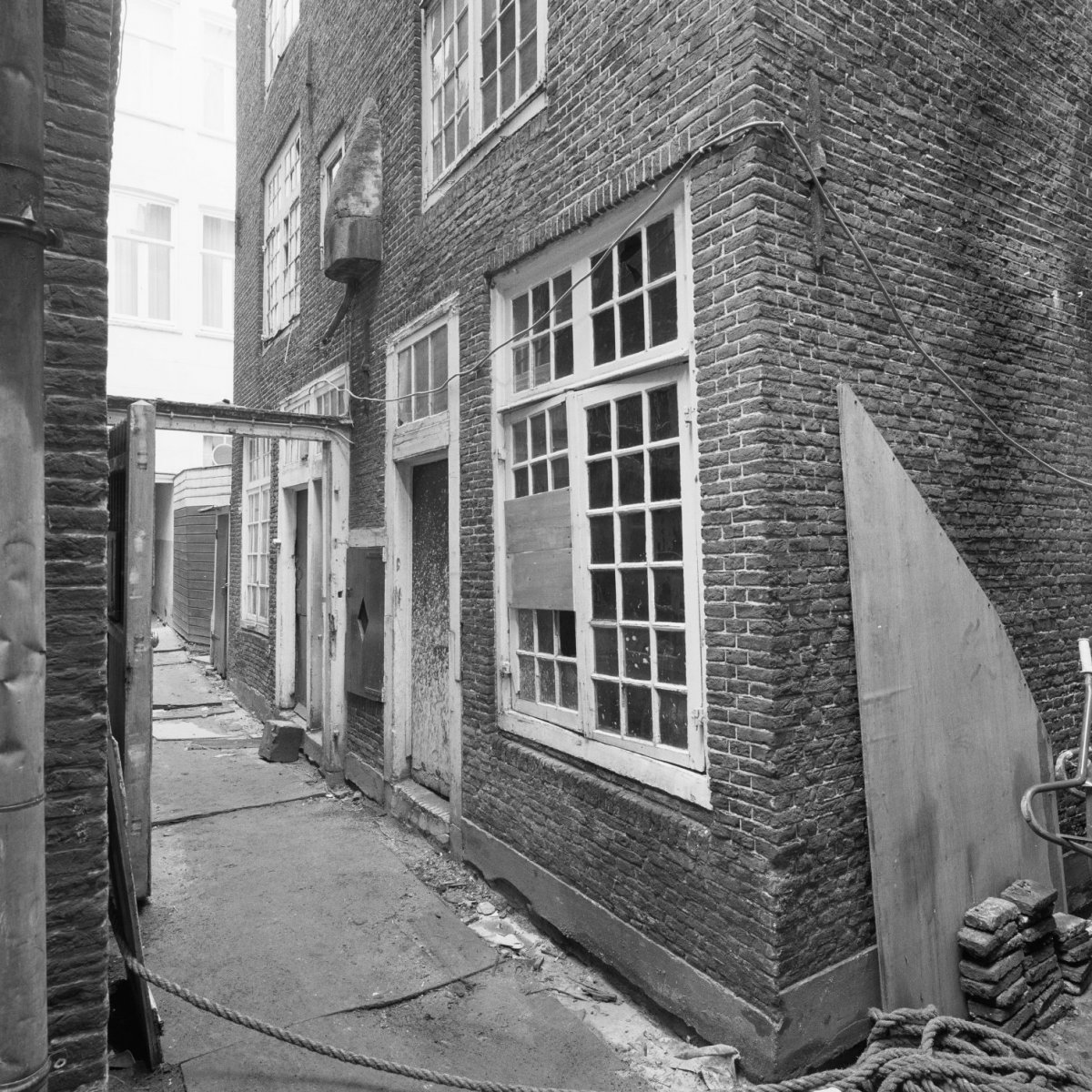

Nothing can be seen of the courtyard on the canal. You enter the door of a seemingly ordinary house, but instead of a vestibule, you enter a low stone corridor. At the end of it is a gate with a brass bell. Behind that fence, the courtyard lies like a small village. The streets are so narrow that you can easily shake hands with your neighbour from the window.

In April 1943, Henk came home to the Suykerhofje and found the gate open. Fuming, he ran through to the old bleaching field to find out who made such a mistake and was arrested on the spot by a plain-clothed S.D. (German Security) officer. He was sent to a prison on the Dutch coast and then to a POW camp in Germany, where he remained until the end of the war. Bram Kuipers, a 21-year-old biology student, moved into Henk's room but was arrested shortly afterward while checking certain points of an escape route for reliability. He was imprisoned and then executed, just a few days after his 19-year-old brother Sape, who was also in the resistance.

This is where Bob Hanf comes in. In June 1943, Bob moved into Henk's former room after Bram was arrested. He was not known as Bob, but rather Christiaan Philippus Spinhoven, or, Spin to his roomies. Spin was older than the rest, nearly 50. No one knew he had been awarded a music prize in 1941 from the city of Amsterdam or that he was an accomplished painter, sculptor, and writer because no one knew he was Bob.

In a post-war interview, Herman the Prior describes Spin's arrival to the community:

In the monastic seclusion of our courtyard, where the time is indicated by the carillon of the Westertoren [the same bell that Anne Frank used to count time], we lived rather primitively, with seven or eight, very close together, and yet each doing activities that were hardly mentioned. Activities, which had never become entirely clear, even later. We were separated from the city of Amsterdam by a heavy front door on the canal, accessed by a paved corridor of a few metres and by a large wooden gate. The gate fell with a reassuring click in the lock behind whoever went in or out. Behind the fence, topped by a large lantern to illuminate the street in front and behind it, we lived in a world of our own for many years. One evening, just after the third year of our occupation, someone ushered in Spinhoven, a somewhat peculiar older man: Would you be okay with him coming to live with us for a while? He can get Henk's former room, where Bram lived until recently.

He was a quiet man, and they hardly noticed he was there. After a while, he began to join the group meals and lively evening discussions around the woodstove in the chapel. We had endless reflections on 'what it was like' and about 'how it should be' when finally, 'all this' would be over, Herman reflected during the interview. We had only just grown up, and we clung to each other, sometimes a bit cramped, in order to keep it up, to stay cheerful. The gentle man listened to their political debates, chiming in here and there with a bit of wisdom. We soon got to know him a little more. We grew fond of his company, said Herman.

In the chapel during the war. Herman is on the right, Dick van Stokkem, another resistance worker, is on the left.

Photo credit - De Engelbewaarder magazine #24 Society for the Friends of the Amsterdam Literary Cafe.

In the chapel stood an old piano, and one day Spin arrived in a bulky suit, carrying a briefcase. From the suit-jacket, he pulled a violin, and from the briefcase, sheet music. He knew that Herman played piano, and he had asked a friend to drop by with his cello. I only brought a few pieces of music with me. Do you want to play some of that? It's for advanced players, and I think with some practice, it will go well. Spin had announced, then we can play together from time to time to clear our minds. And then they played, doing their very best to keep up with Spin, who, with a raised voice, yelled directions or courage. Near the end of Herman's interview, he muses - that memorable afternoon, I could have guessed spontaneously that Spin really was a musician and not just musical, like us. But that insight passed me by.

I'll let Herman finish his story about Spin:

There were many moments afterwards where we made music with him in the quiet seclusion of our unforgettable courtyard. "It doesn't sound bad here at all, and I didn't expect anything else." Spin had said with satisfaction. He read Shakespeare and translated Anatole France poems. It made us truly grateful that the long nightmare had brought us together. On April 23, 1944, the S.D. raid came to disrupt the peaceful tranquillity of the Hofje. Early in the morning, five men with and without uniforms stormed down the alley, yelling for entry. What they were looking for was never made clear, but they found Spin. What we had never wanted to know exactly, during all those months, they had sorted out in no time. Much later, someone was able to tell me who Christiaan Philippus Spinhoven actually was.

Bob Hanf was deported to Auschwitz where he was murdered on September 30, 1944.

When Arthur and I were next in Amsterdam, we searched for the Nieuwe Suykerhofje. Arthur pulled out his phone, and we explored maps, looking for those tell-tale orange roofs. I recognized them right away. We stopped in front of a canal house with two front doors, one sporting several addresses - this must be it! But it was locked up tight. I shrugged in defeat as a woman walked up, jingling a key. Excuse me! said Arthur, and he quickly summarized the Bob Hanf story. Well, this is a remarkable story, said the woman, but we are forbidden to let people enter. She must have seen our disappointment because she continued, Hmm, I am moving out tomorrow – so, perhaps no harm can come to me by letting you in. A resident breaking the sacred rules! She unlocked the door and motioned us into the low stone corridor. We walked through the darkness, into a narrow alley flanked by tall houses, and under a gate topped by a lantern large enough to illuminate the street in front and behind it. A man stepped aside to let us pass, but the woman stopped and began to tell him the story, and then turned to Arthur. You finish, she said, and then disappeared up a steep stairway. There was a chapel then, said Arthur, glancing around but not seeing what he was looking for. There still is, said the man, I live in it. I'd be happy to show you around.

The Nieuwe Suykerhofje remained a rental complex for more than 50 years after the war. Several renowned Dutch artists and writers called it home at one time or another. When Henk and his daughter went back in 1996, a well-known musician-composer-actor-author (you name it, he did it, wrote my pen-pal) lived in the chapel. In 1999 it was again near ruin when a developer purchased it and carefully restored and preserved whatever he could while making just five apartments out of the 27 rooms plus chapel. The original floor and wall tiles are still there. Ancient fireplace mantels grace the bright rooms, and the structure of the box-beds can be seen in the architectural details. In the chapel, now a living room, large windows shed light into the lofty room where the old piano once stood. French doors open onto a small terrace, part of the original bleaching field, creating the ambiance of a regal garden house, albeit with altar. The whole complex is a national monument now, to be preserved and protected, and there are restrictions; no removal of the alter! Our guide led us up steep stairs to the chapel attic, where a hatch is hidden in the floor. We descended through it to a room not much bigger than a closet. This was a hiding place, he said, motioning around to the four walls. I imagined the Jewish people hiding here before heading out on The Swiss Road.

After an hour of exchanging stories and comparing histories, we thanked the current Abbot for his hospitality and walked out through the tunnel returning to the city, closing and locking heavy the door behind us.

Here are some photos of this hidden gem.